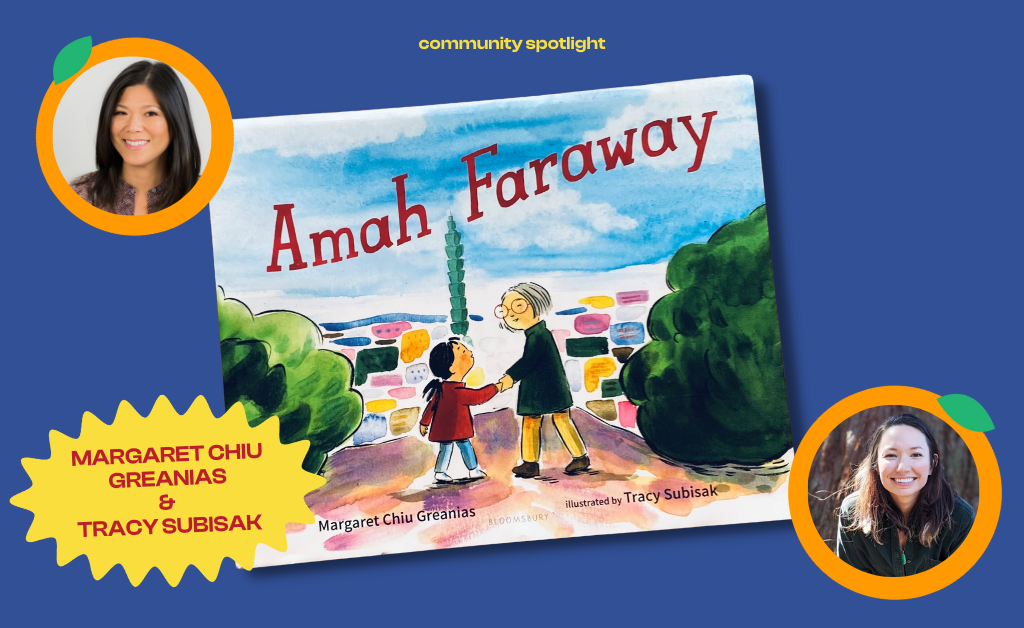

Amah Faraway: Interview with author Margaret Chiu Greanius and illustrator Tracy Subisak

🍊 As we enter another Lunar New Year holiday season during this pandemic, a good amount of us are still likely separated from our loved ones, particularly those overseas. The latest book by Bay Area Taiwanese American children's book author Margaret Chiu Greanias, Amah Faraway, beautifully illustrates a relatable tale on maintaining family connections across distance, language, and cultures. We had the pleasure of interviewing Margaret and illustrator Tracy Subisak to hear more about their experiences growing up and staying rooted with their families.

Here's a little bit about the book:

Thank you so much for taking time to share your story with us! Margaret, what inspired you to write Amah Faraway?

MARGARET: My memories of my Amah (the Taiwanese word for grandmother) are some of the strongest from my childhood. She was the only grandparent I knew growing up and she embodied all of my grandparent hopes and dreams.

But our relationship wasn't easy. We saw each other infrequently since we lived so far apart--maybe once per year or two. My Taiwanese was about as good as her English which is to say not very. We were immersed in our own cultures and customs. All of this only created distance between us.

Even so, I adored my Amah. It just took a bit of time for me to feel familiar with her whenever she visited. I would go from hanging out nearby as I listened to my mom and her catch up to hanging onto her hand all the way to the departure gate at the airport, at some point having overcome my feeling of distance. I noticed my children go through something similar when they first visited Taipei. They went from wondering why we had to go to Taiwan in the first place to wondering when we could go back. Whenever I was looking for a new story to write, this idea of feeling distant which grew into feeling connected came up over and over again. But I never knew how to put it into a story until I wrote Amah Faraway.

For many Asian immigrant families in the diaspora, visiting a homeland to reconnect with their roots is oftentimes a rare privilege. This book taps into the challenges of connecting, reconnecting, and remaining connected across generations and cultures. What did you want readers to take away from the book?

MARGARET: For diaspora who are immersed in the culture of an adopted home, I think it's only natural that we might feel disconnected from our faraway family, the culture we've inherited, and our ancestral country. When I was growing up, the focus was fitting in and trying not to be othered. I went to Chinese school reluctantly, refused to try Taiwanese treats like pineapple cakes (now I know they are delicious!), and didn't feel like Lunar New Year was my holiday. Now though, after having my own children, I've realized the importance of staying connected to our roots--especially because as Asian Americans, our heritage is inseparable from how the world sees us.

I'm hoping Amah Faraway will resonate with those who have felt a disconnect from faraway family and/or their family heritage and that young readers will see how one moment of being open to something "new" led to hope, happiness, and connection for Kylie.

TRACY: One of the things I really connected with in this story was how quiet and intimidated Kylie is when she first visits her Amah. I envisioned her glued to her mom during the first half of the book, because that’s exactly how I was whenever my Waipo (what I called my Taiwanese grandma) visited our home. Waipo and I had a communication barrier and as a kiddo I had anxiety about speaking Mandarin poorly. But we were always able to find comfort in delicious food eating together!

This book is a great way for kids, and their parents, to identify the challenges in connecting and reconnecting with faraway family and culture—that disconnect can feel strange and intimidating at first, but there’s such comfort and love to be found after taking the time to identify those commonalities. It’s also a great conversation starter in finding ways to maintain that connection, especially in the midst of the travel challenges of the past couple of years.

Can you share your own journeys to reconnecting with your roots and heritage?

MARGARET: My journey to reconnecting with my roots and heritage has been piecemeal, and I still have a lot of work to do. Since having children though, I have a new curiosity about our heritage. I want my children to feel pride in our roots, which is inseparable from our appearance.

On some level, Taiwanese culture has been engrained in me simply by the way my parents, who are both Taiwanese immigrants, raised me. But for me, many of the customs we followed growing up lacked context. For example, why the adults always fought for the chance to pay for our shared meal, what the purpose of red envelopes was, and why certain family members spoke Japanese. Lately, I've been listening to a podcast called Hearts in Taiwan hosted by Annie Wang and Angela Yu. Hearts in Taiwan is all about exploring the history of Taiwan and Taiwanese culture. While listening to the podcast, I've had many aha moments about my family's culture and history. I've also realized I never asked my parents why we did things the way we did, and my parents never explained our customs in detail.

Writing stories inspired by my childhood experiences has also helped me reconnect to my roots. It requires I clear the cobwebs from my brain and recall tangible details from childhood--like the feel of the paper in my Amah's bookstore in Taipei, the smell of burning joss sticks when my mom held a ghost meal, and the ooey gooey-ness of ba wan (Taiwanese meatballs). It makes me miss Taiwan and long to visit.

Recently, I've realized I never had a full picture of who my parents are. When I was growing up, they were focused on making sure I had enough to eat and that I was getting good grades. They rarely spoke about their own pasts. As they grow older, I'm feeling the urgency to learn all I can about them, their pasts, and our family history. Just a few months ago, my father shared with us a family tree that traced back ninety-five generations! My children were in awe and it was so wonderful to see their pride in our family.

TRACY: When I was a kid going to Chinese school on the weekends, I was the only half-Taiwanese kid in the entire school (minus my big brother). Even though I loved all my friends at Chinese school, and the cultural classes—ribbon dancing, gongfu, cooking, etc., my language skills were sub-par. I ended up dropping out in elementary school.

It wasn’t until I enrolled in the Chinese class my mom taught at my middle school that I started to really “get” the language. I know not a lot of AAPI have the opportunity to learn their mother tongue in an institutionalized way, and I’ll always cherish the enthusiasm my mom had for teaching Mandarin, the history of the language, and the many aspects of Chinese and Taiwanese cultures.

Language has been a key for me in connecting with my heritage, especially during my travels in my adulthood. I didn’t go to Taiwan until I was in college, based on a family superstition that stemmed from all my cousins and my brother ending up in the hospital in some random way during their first visit to Taiwan! I was lucky to spend time studying Mandarin and taking culinary classes at the Mandarin Training Center at National Taiwan Normal University after I graduated from college. I loved living in Taiwan so much that I ended up finding my first job at Pegatron in Guangdu, Taiwan. I shared the low-key, yet hard-working lifestyle and goofy humor with the people there—I felt like I was home. Ever since I moved back to the States, I’ve sought out the local Taiwanese community to stay connected.

Why do you think it’s important to stay connected to your heritage?

MARGARET: As Asians, whether we feel connected or not to our roots, other people will associate us with our heritage. It's in our best interest, especially in this time of AAPI hate, to be able to dispel untruths and pull together to support and find strength in each other.

On a more personal level, I believe it's important to stay connected to our heritage because it's something that grounds us in our identities. For diaspora, our families might be split between new and old countries. Staying connected to our culture means a better understanding of each other which leads to more empathy and ultimately brings both family in new and old countries closer together. Heritage also helps tie us together as a community and provides a sense of belonging which is so important for mental health and emotional well-being.

TRACY: Ever since my mom passed away five years ago, I’ve felt the connection to my heritage slipping through my fingers. My mom was such a huge part of my Taiwanese identity and connection to the language. We would talk a few times a week in Chinese, and she had the patience with me to advance and maintain my language skills.

My half-Taiwanese appearance is often described as “ambiguous,” and I have frequently felt a need to prove myself worthy of my heritage. Recently, I have had to really dig deep and advocate for myself and my identity and have tried my best to lean into my connections with my heritage by taking steps to be more involved in the Taiwanese community in the Pacific Northwest.

What were both of your journeys to writing and illustrating children’s books?

MARGARET: When I was little, I would check out a huge stack of books at the library and read them all in one sitting. But being an author didn't even register to me as something I could do. I was more focused on traditional careers like being an accountant or an architect. Only when I had to fulfill an elective requirement during my last year in college did I take a class in creative writing. I discovered that I loved it. Still, when I graduated, I stayed busy with other things—working in marketing and eventually earning my MBA. Once I started having children though, I rediscovered picture books. I think I loved reading them more than the kids loved listening to them. With nothing better to do while nursing my second child, I began thinking of story ideas. Eventually, I wrote my first story. Then, I joined the Society of Children's Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI), discovered the kidlit community, found a critique group, took a bunch of classes and workshops, and began writing story after story.

TRACY: I studied industrial design at the University of Cincinnati, and have drawn characters and made up little worlds for as long as I can remember. I ended up working at Intel when I moved back to the States after working in Taiwan, and everyone I worked with asked me to draw out storyboards to help explain how their designs might be used. It was then that I finally took a children's book storytelling course from Victoria Jamieson (yes, Roller Girl, Victoria Jamieson) at PNCA. And it was Vicki who told me that this career was a viable option for me. The seed was planted, and I worked on my children’s book illustration portfolio every night after work until I had some signs telling me it was time to go for it full-time! I was lucky to meet a wonderful group of friends at a chapter of SCBWI at the start of my journey and we have all supported each other as we navigate the industry and improve our craft.

Tracy, can you share what inspired the visual style of your illustrations?

TRACY: Working on Amah Faraway may have been the first time where I’ve felt truly confident in my painting and inking style. When I compare my collective few months of studying Chinese calligraphy and painting to my mom’s and her family’s years of daily calligraphy practice… does it even compare? Well, my eye and appreciation is still there at least.

My painting style is a bit of a fusion of all the different styles of painting that I’ve ever learned— from utilizing the vast breadth of paint strokes that can be achieved with a Chinese brush to finding a balance between shape and line when it comes to pulling the focus of the eye.

I wanted to capture the movement and bustle of the night market scenes, the pause of overwhelm from Kylie when she’s at her first big banquet, the moment when she connects with her Amah at the hot springs. It helps that I connect so thoroughly with this story emotionally and spatially— with a deep love for the matriarchs in my life, but also I freaking love Taiwan and every detail I’ve put in there has had at least a moment of curiosity from me in Taiwan at some point of my life.

A question we ask everyone (for our namesake), what would you say is your favorite fruit? And do you have any favorite cut fruit memories to share?

MARGARET: I love sweet, juicy white peaches and crisp, delicately sweet Asian pears.

After dinner, we'd rarely get desserts like ice cream or cake. Instead, my mom would cut fruit. So I always associated fruit with dessert. But that was okay because I loved and still love fruit today (and it's guilt free too!).

TRACY: So, so many.

An obvious fruit favorite is the mango. Specifically, a mango grown in Taiwan that is ripe every June for a two-week period. I wish I could tell you the name of it, but all I know is that my late-mom, Aunt, and Uncles are all obsessed. It’s small, easy to peel, and has a small seed, which equals a high fruit meat-to-seed ratio. The goal during this mango’s season is to eat as many as possible, and cherish each juicy bite.

One June, I was in Taipei for a business trip, and one of my uncles happened to be in town too. While I waited at a very specific bench for him to pick me up to go see Waipo in Sanzhi, he zoomed past me and slammed on the breaks at the next bench 20 feet further. Of course, this was very inconvenient for him, and after waiting for me to saunter to his car, we were off!

It’s important to bring at least three bags of fruit to Waipo and her caretaker, so we stopped by the fruit stand in Danshui on the way. We got at least two bags full of those special mangoes among other bags of fruit and vegetables.

When we got there, Waipo was finishing up her nap, so we waited in the hallway listening to the cicadas outside. Uncle pulled out a bag of mangoes and handed me one. I took it to my mouth and pulled the skin off gently with my teeth, then took my first bite—juicy pulp was dripping everywhere. I looked up to grab a napkin and saw that Uncle had finished FIVE mangoes within my first bite. “快點! (Hurry up!)” he said, as he wrapped up the bag of mangoes and got up to go inside. A tiny tear fell inside my soul as I had to rush to finish off my favorite fruit!

My Uncle’s speed of mango eating and that moment are forever intertwined with those mangoes!

Be sure to find a copy of Amah Faraway at your local bookstore or order online through this link.